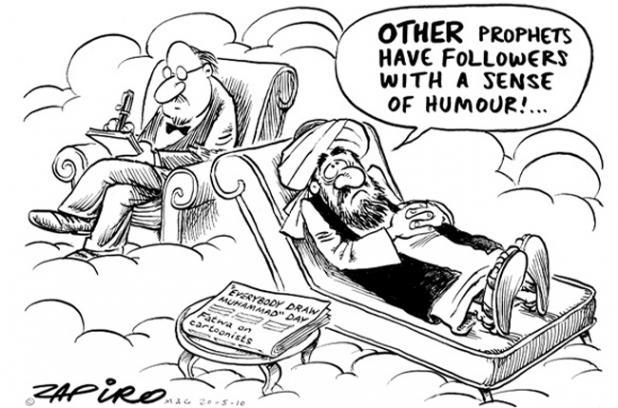

Jonathan Shapiro (a.k.a. Zapiro) is an equal opportunity offender – that is, if you like to think of what he does as offensive at all. There’s no doubt that some people have been, and are, offended by some of his cartoons, but that is a separate matter from whether they are in fact offensive, objectively speaking.

His role as a social critic and commentator leads him to sometimes poke at open wounds, yes, but almost always in a way that reveals the underlying prejudices that cause significantly more harm than any harms caused by the cartoons themselves.

The cartoons challenge their audience to reflect on whether their feelings of outrage are justified, and also whether others – like Zapiro – may be justified in feeling that there is something worth critiquing, challenging, and even sometimes mocking, in opinions and beliefs that we sometimes take far too seriously.

© 2010 Zapiro

Printed with permission from www.zapiro.com

For more Zapiro cartoons visit www.zapiro.com

Targets of his satire are drawn from a pool which has historically admitted just about anyone, and anything. If he has an axe to grind, that axe is most likely composed of inflated egos, undeserved reputations, malfeasance against the equal treatment and dignity of all – no matter how rich or poor, influential or invisible.

We should remember that critics of this sort, who offer a courageous perspective on current events, and try to point out details that we might be missing, serve an enormous public good. It’s very easy for all of us to end up with our heads buried in the sand, or stuck up our own (or another’s) backsides to the extent that we forget that our outrage may be ill-construed or illegitimate.

Today, Zapiro’s cartoon for the Mail & Guardian was the subject of a last-minute attempt to stifle press freedom. The Twitter feed of the unfolding events makes for interesting reading, in that Molana Bam’s primary argument appears to be the standard one where representations of Muhammad are concerned – namely, threats of violence.

Not directly, but nevertheless, the cartoon is a “threat to harmony”, and “stirs emotion”. A much larger threat to harmony, perhaps, is the struggle involved in reconciling Bronze Age beliefs with the modern world, and the curious tolerance that it requires those of us who try to govern our lives according to knowables. Tolerance, that is, of beliefs that are shared by fanatics who try to kill cartoonists and authors who represent aspects of that belief.

If you are a believer who is not inclined to fanatical – and criminal – action, you certainly should feel aggrieved when cartoons like this are published. But the cause of your aggrievement should be your less civilised brothers and sisters, who make such comment necessary – not those who make the comments.

The points made by Zapiro, as well as by past examples of this same issue, are a reminder to you to get your house in order, so that there is no longer any need to mock or ridicule.

You do this most effectively from the inside, by persuading people who take faith as a way to justify paedophilia, homophobia, oppression, murder, censorship and all sorts of other social ills that they have lost their way, and that surely a god worth taking seriously would not want you to do those things.

Two responses to the issue worth reading: Nic Dawes, Mail & Guardian Editor; Jordan Pickering (a Christian response).