There’s an interesting – and important – discussion going on in South African professional philosophy at the moment. You can read about it on the Mail&Guardian, but the nutshell summary is that tensions regarding the “apparent supremacy of European philosophy over African philosophy” have resulted in the president and “several black philosophers” resigning from the Philosophical Society of Southern Africa (PSSA).

Category: Headspace

Often abstract thoughts on things that don’t necessarily hinge on any contemporary events.

As Africa Check reports in Daily Maverick, it’s not yet clear what the effects of the proposed sugar tax in South Africa will be. But it is clear that South Africa has a serious obesity problem – and that sugar is a clear causal factor for obesity.

A Mail&Guardian journalist recently approached me for comment on this (I’ll update this post with a link to the piece when it’s published), but because the M&G article will likely only quote snippets, here’s a fuller response to a few sugar tax issues.

The reading material for my “Evidence-based Management” course at the University of Cape Town contains an early draft of what ended up becoming chapter 1 of Critical Thinking, Science and Pseudoscience.

In the book, Dr. Caleb Lack and I argue that phrases like “everybody is entitled to their opinions” are typically trite or misleading.

In the book, Dr. Caleb Lack and I argue that phrases like “everybody is entitled to their opinions” are typically trite or misleading.

They can be meaningless, in the sense that of course it’s true that everyone is legally entitled to hold whatever opinions they like.

This doesn’t seem to be what we mean when using the phrase, though – we typically say: “well, you’re entitled to your opinion” precisely when an opinion has been expressed, where we disagree with the expressed opinion, and where we express that disagreement by using the phrase in question.

The Mail&Guardian recently published an op-ed telling readers that the paper would no longer italicise words in South African languages other than English (for the benefit of foreign readers, we have 11 official languages here).

You can read the piece on the M&G website, but you’ll need to create a (free) account to do so. While I understand, and have great sympathy for, their motives, the reasoning is muddled, and the conclusion incoherent.

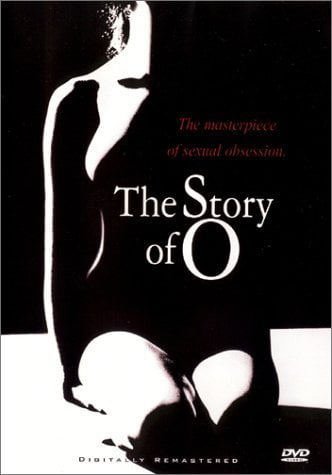

The Story of O is commonly considered to be a pornographic novel. As with any artwork that challenges moral sensibilities, a “pornographic” novel expose us to things that are morally abhorrent to us, while simultaneously leaving us uncompelled to condone what is described.

The Story of O is commonly considered to be a pornographic novel. As with any artwork that challenges moral sensibilities, a “pornographic” novel expose us to things that are morally abhorrent to us, while simultaneously leaving us uncompelled to condone what is described.

The interesting thing about The Story of O, for the purposes of this post, is that the brutality and abuse that O is subjected to seem to actually be morally acceptable in the fictional world of the story.

And herein lies my focus: is The Story of O, or any work of literature that has an implicit moral stance which we find unacceptable, to be valued less as a work of literature because of its unacceptable moral stance?

Second, should the fact that one or more of us feel outrage at something in an artwork mean that the artwork should not be shown, produced or performed?

The contemporary example that made me want to air these issues is the Estonian composer Jonas Tarm, who had intended to play “Marsh u Nebuttya” (“March to Oblivion”) at Carnegie Hall a few weeks ago.

The Carnegie performance was cancelled, after

it was brought to the administrators’ attention, in a letter of complaint signed “a Nazi survivor,” that the piece incorporates about 45 seconds of the “Horst Wessel” song, the Nazi anthem.

This, despite the fact that that the “Horst Wessel” song has been used in various compositions for many years, often as negative commentary on Nazism, and was in this piece framed negatively also (via the manner in which Mr. Tarm introduces the segment).

It seems that it was precisely his intention to get people to think about that historical period critically, and perhaps to feel some discomfort while doing so – but political and emotional sensitivities have made that impossible in the Carnegie Hall case.

This is not a judgement on those sensitivities themselves, but more on (as a friend put it) the apparent decline in our ability to interpolate between texts.

The failure of our ability to interpolate, in other words, is our failure to see things in a context, and to play off various texts (including, in the case of “O”, the moral text), off against each other.

More worrying, perhaps, is our conceding to that decline, in setting standards of offence, and what offence legitimises, that cater to serve the interests of those who are most offended (or who can claim to be so).

Victory goes to the most sensitive, which simply serves to incentivise people to be hypersensitive.

The same set of questions arise in terms of the genesis of art – for example, when (if ever) questions about the moral character of the artist matter, regardless of the quality of the art. For example, can (and should) one enjoy art produced by a child abuser, murderer, rapist, etc.?

This issue is, I feel, intrinsically connected to the question of what we value works of art for. It is true that we “possess a capacity to entertain a thought without accepting it”, to quote Malcolm Budd’s paper “Belief and sincerity in poetry”, and to my mind, this capacity is an essential component of enjoying art.

But Budd points out that a reader can enjoy a text “also on account of the poem’s expressing a philosophy that he believes”. If I subscribe to Christian values, I might enjoy Bunyan’s A Pilgrim’s Progress because of the way that text glorifies those values, just as Hitler would probably have derived great pleasure from watching Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will.

But works that can be described as propagandistic, in the sense that they exist primarily for the purpose of convincing the audience of the worthiness of a certain moral stance, are not, I feel germane to this discussion. The reason for this is the categorial intentions of the author.

It seems fair to say that most texts (and here I mean text in a broad sense, to include things like movies), while containing an implicit moral stance, do not exist primarily for the purpose of converting others to that stance. Works that do exist for this purpose may be considered as manifestos, but not as literary texts (for the purposes of this discussion).

So a movie such as Triumph of the Will may be viewed with distaste in the same way as we might view a swastika with distaste, while a text that can be more broadly conceived as containing a moral stance which we may find offensive, without actually having been conceived for the purpose of promoting it, should not be viewed with distaste for the same reasons. To do so would be, I feel, a type of category error.

If we set the bar at “someone could find this morally offensive”, the problem would be that is becomes impossible to find a text that has any objective (or at least, non-partisan) artistic value.

And that some texts have value, considered solely as literary texts, is a thesis which seems intuitively correct – they can make us feel, or make us think, as independent virtues regardless of their (for example) propagandistic value.

While it’s true that the moral or political stance of the audience often precludes the possibility of reading the art “on its own merits”, those merits have to include more than simply those stances.

And while there are contexts in which things are clearly simply abusive towards an audience, or only intended to provoke without additional artistic intent, the fact that we – or some of us – can’t read art in a context, outside of our subjective sensitivities, seems to be a deficiency of and in the audience, rather than in the art.

Speaking on related issues to these, the author of the New York Times piece linked above says (in relation to Mr Tarm’s composition):

I’d like a chance to think about [these issues] for myself. The New York Youth Symphony should program “Marsh u Nebuttya” on its next Carnegie program and give me, and the rest of the audience, that opportunity.

Precisely. These questions are sometimes not easy, but we get no closer to answering them by refusing to allow them to be asked.

I don’t know about you, but I’m finding that the news cycle – especially here in South Africa – is hitting fresh heights of bonkers-ness just about every day. And where scandalous news emerges, outrage on social media follows.

Outrage is oftentimes merited, and you should please not read this post as a complaint about people getting upset about things (although, as David Mitchell points out in a characteristically amusing column, it might be a problem that outrage has become our default setting).

More important than the outrage itself is the motivation for the outrage, in both senses of motivation – the originating argument or cause of it, and then the retrospective justification of it, where I think too many of us are operating in bad faith.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the concept of the “principle of charity”, Wikipedia’s entry opens with: “In philosophy and rhetoric, the principle of charity requires interpreting a speaker’s statements to be rational and, in the case of any argument, considering its best, strongest possible interpretation.”

To put this into practice, one strategy might be to apply Rapoport’s Rules, summarised by Daniel Dennett as follows:

- Attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly and fairly that your target says: “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.”

- List any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

- Mention anything you have learned from your target.

- Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

But instead of taking this approach, much online commentary, whether in the short-form of Twitter or in blogs and columns, seems to be a frantic dash to demonstrate the evil of your opponent’s point of view.

There are important debates going on about left-wing politics, political correctness and what counts as fair and unfair criticism. It’s important that these debates aren’t won by those who claim that being offended is always a trump card, because that a) incentivises victimhood and b) is a race to the bottom for what entitles you to claim protection from offence.

It’s good to be challenged – we are often wrong (regarding science, for example), and need to be told so. But how we tell each other that we’re wrong is the problem, in the sense that if you criticise from a position of assumed certainty that you’re right, and your opponent wrong, nothing good is likely to come from the interaction.

I’ve so far stayed out of the Jonathan Chait debate that was occupying so many people in (the broad and very difficult to define) online political community I belong to. There are far too many triggers for hostility in the issues he raises, with a concomitant low probability of sober reflection on the issues.

But now that the fire of that debate has gone out, I do want to point you to his piece responding to his critics, in which he (rightly) reminds us that the fact that some people complain about political correctness simply as a way to excuse or mask their bigotry does not mean that others might also take offence too often, and for the wrong reasons (for example, the race or gender of the speaker, regardless of what the speaker is saying). To quote an important passage from that piece,

making distinctions is important and valuable. Voting may present us with limited and imperfect choices. But when we analyze the world, we don’t need to restrict ourselves to binary choices. We can oppose both racism and inappropriate responses to racism. Indeed, that kind of multifaceted thinking is a special responsibility for liberals.

Having begun this post with a vague allusion to issues in the South African political landscape, let me close with the specific case of the City of Cape Town having approved the renaming of a road in honour of the conservative apartheid-era president, FW de Klerk, who can among his achievements apparently count ordering the murder of 5 children (and a Nobel Prize).

Having begun this post with a vague allusion to issues in the South African political landscape, let me close with the specific case of the City of Cape Town having approved the renaming of a road in honour of the conservative apartheid-era president, FW de Klerk, who can among his achievements apparently count ordering the murder of 5 children (and a Nobel Prize).

I was one of the handful (around 250) that opposed the renaming during the consultative process, while around 1700 wrote in support of it. My reasons for opposing it were offered in a previous post, so I won’t rehash them here. But I do want to say something about last week’s council meeting, at which the City approved the renaming (initially proposed by this group of “prominent Capetonians“).

According to news reports, (at least) two quite disturbing things happened at this council meeting, to which I’d add one example of the language of politics gone utterly mad.

Disturbing thing number one is that our Mayor, Patricia de Lille, was apparently taunting ANC councillor Tony Ehrenreich by waving a red clown nose in his general direction whenever he spoke, and accusing him of engaging in “clown politics”. To my mind, if the Mayor engages in debate as if it’s happening on a school playground, there’s more than one person playing “clown politics”.

@PatriciaDeLille I'm no fan of @TonyEhrenreich, but for as long as my Mayor is waving clown noses about, I'll be skeptical of good faith.

— Jacques Rousseau (@JacquesR) January 28, 2015

More disturbing, though, is this detail of how the council meeting proceeded (my emphasis):

The ANC then asked to caucus and, on their return to the chamber, found that the meeting had proceeded without their input. ANC councillors were outraged. The Speaker’s calls for order were drowned out by ANC councillors banging on desks while chants of “no” rang out. Smit then ordered the ANC to leave and the hall to be vacated.

The council sitting was moved to another room, with many DA councillors also shut out as metro police blocked ANC councillors from getting in. Chaos erupted when ANC members tried to force their way in, resulting in a tussle between some ANC councillors and metro police officers. There was continual shoving and pushing as ANC councillors tried to storm the room.

For the next two hours, ANC councillors tried to get in while remaining DA councillors were gradually escorted into the room, where ACDP and FF Plus councillors participated in the discussions.

I’m sympathetic to the DA and de Lille’s claim that the ANC might sometimes act in ways that are aimed at making the City “ungovernable”. But when you’re taking a decision regarding renaming a road after an apartheid president, in a city perceived by some as being racist, it’s quite mad – in terms of effect on public perception – for only the DA, ACDP and FF Plus to be debating the motion and making the decision (a separate issue to whether they were quorate, which they were).

Furthermore, if the meeting did proceed while the ANC was taking a break to caucus, that indicates serious bad faith on the part of the Democratic Alliance, in that they don’t give any impression of being interested in engaging with the ANC or Ehrenreich’s arguments.

In general, that’s the problem I’m highlighting in this post, in full awareness that doing so is hardly novel. But for those of us that care about debate, and its value in showing us where we’re wrong (which is essential to becoming more often right about things), the occasional reminder of why we do this, and how to do it, hopefully serves a purpose.

In our little corners of the Interwebs, or in meatspace, we can do better than simply yell at each other, or presume malice in others before we’ve even bothered to try and understand what they are saying. It’s difficult, to be sure, and I often fail at it myself. But not doing so, or giving up trying, simply cedes all public discussions to the idiots and the ideologues.

In closing, on the Humpty Dumpty language of politics, consider this quote from the Mayor of the City of Cape Town, on the ANC’s opposition to the above-mentioned street renaming:

[The ANC] are opposed to progressive politics and anything that is not backward-looking and embraced by the cold hands of racialised politics.

Renaming a road after an apartheid president is “progressive politics”? As a friend said on Facebook, “Yup, what self-respecting revolutionary could be against honouring a freedom fighter like FW? I want to cry.”

A few weeks back, Sarah Wild asked if I’d be interested in offering a comment or two on artificial intelligence for a piece she was working on (the article in question appears in this week’s Mail & Guardian).

A few weeks back, Sarah Wild asked if I’d be interested in offering a comment or two on artificial intelligence for a piece she was working on (the article in question appears in this week’s Mail & Guardian).

While I knew that only a sentence or two would make it into the article, I ended up writing quite a few more than that, and offer them below for those interested in what I had to say.

What role to humans have to play in a world in which computers can do everything better than they can?

In the most extreme scenario, humans might have no role to play – but we should be wary of thinking that we’re somehow deserving of playing one in any event. While it’s common for people to think of themselves, and the species, as both special and deserving of special attention, there’s no real ground for that except our high regard for ourselves, which I think unfounded. We don’t “deserve” to exist, or to thrive as a species, no matter how much we might like to. If the planet as a whole, including all sentient beings, would be better off with us taking a back seat or not existing at all, those of a Utilitarian persuasion might not think that a bad thing at all.

In a less pessimistic (for some) scenario, we’re still a very long way away from a world in which humans are redundant. Computers are capable of impressive feats of recall, but are significantly inferior to us at adapting to unpredictable situations. They’re currently more of a tool for implementing our wishes than something that can initiate and carry out projects independently, so humans will – for the foreseeable future – still be necessary for telling computers what to do, and also for building computers that are able to do what we’d like them to do more efficiently.

Elon Musk has said that AI offer human kind’s “greatest existential crisis”. What do you make of this statement?

This strikes me as bizarrely technophobic. We’re already at a point – and have been for decades – where the average human has no idea how the technology around them operates, and where we routinely place our faith in incomprehensible processes, machines and technologies. (Cf. Arthur C. Clarke’s comment that sufficiently advanced technology is “indistinguishable from magic”.) If it’s a level of alienation from the world we live and work in that triggers this crisis, I’d think we’d be in crisis already.

There seems no reason to prefer this moral panic or fear-mongering to what seems an equally plausible alternative, namely that the sort of alienation Marx was concerned about might be alleviated through AI. If machines can perform all of our routine tasks far more quickly, efficiently and cheaply than we currently can, perhaps we can spend more time having conversations, walks and dinners, rediscovering play over work, or generating art.

It’s probably true that there will be an interregnum wherein class divides will accentuate, in that wealthier people and nations will be first to have access to the means for enjoying these advances, but as with all technologies, they become cheaper and more accessible as our research advances. Technophobia as displayed by Musk here runs contrary to that, in that the last thing we want to do is to disincentivise people from engaging with these technologies through making them fearful of progress.

A recent Financial Times articles paints an apocalyptic AI future. What do you think a future world – with self-driving cars, care-giver robots, Watson-driven healthcare, etc – looks like?

The key fears around an AI future tend to be driven by the concept of the singularity, popularised by Ray Kurzweil. One possibility sketched by those who take the singularity seriously is that if we invent a super-intelligent computer, it would be able to immediately create even more intelligent versions of itself – and then this concept, applied recursively, means that we’d soon end up with something unfathomably intelligent, that might or might not think us worth keeping around.

Again, I think this pessimistic. We’d be building in safeguards along the way (perhaps akin to Clarke’s laws of robotics), and we’d likely see frighteningly smart computers coming years or decades in advance, allowing us to anticipate, to some extent at least, what safeguards would be necessary. Given the current state of AI, we’re so far away from this possibility that I don’t think it worth panicking about now (despite Kurzweil’s claim that the singularity will occur in 30 or so years from now).

(Incidentally, Nick Bostrom is very worth reading on these things.)

A more general reason to not be as concerned as folk like Kurzweil are is that I’d think malice against humans (or other beings) requires not only intelligence, but also sentience, and more specifically the ability to perceive pains and pleasures. Even the most intelligent AI might not be a person in the sense of being sentient and having those feelings, which seems to me to make it vanishingly unlikely that it would perceive us as a threat, seeing as it would not perceive itself to be something under threat from us. (A dissenting view is here.)

But to address the question more directly: such a world could be far superior to the world we currently live in. We make many mistakes – in healthcare, certainly when driving, and it’s simply ego that typically stands in the way of handing these tasks over to more reliable agents. Confirmation bias is at play here, and also mistaking anecdotes for data, in that when you react instinctively to avoid driving over a squirrel, the agency you feel so acutely feels exceptional, and validates fears that the robot driver might make the wrong choice (perhaps, sacrificing the live of its passenger to save other lives). On aggregate, though, the decisions that a sufficiently advanced AI would make would save more lives, and we are each individually typically in the position of the aggregate, not the exceptional. I therefore would think it immoral to not opt for robot drivers, once the data shows that they do a better job than we do.

(An older column about driverless cars, for more on this.)

What you do think is the most interesting piece of AI research underway at the moment?

On a broad interpretation of AI, I’d vote for transhumanism, without a doubt. We’ve been artificially enhancing ourselves for some time, whether through spectacles, doping in sport, Ritalin and so forth. But AI and better technology in general opens up the possibility for memory enhancement (one could perhaps even rewind your memories), or for modulating mood, strength and so forth. Perhaps these modifications will occur with the help of an AI implant, that modulates some of your characteristics in real-time, in response to your situation.

This would fundamentally change the nature of humans, in that we’d no longer be able to define ourselves as persons in the same way. Who you are – the philosophical conception of the person – has always been a topic of much debate, but this would detach those conversations from many of the factors we take for granted, namely that you are your attributes, such as the attribute of being a non-French speaker (with the right implant, everyone is a French speaker in the future).

It would also likely change the nature of trust, and relationships. Charlie Brooker’s “Black Mirror” TV series had a great episode (The Entire History of You) on this topic, suggesting that it would be catastrophic for human relationships – nobody would be able to lie about anything. It is this area (of human enhancement via AI/tech), rather than autonomous AI, that I think potentially far more worrisome.

But to answer your question more directly – neural network design is going to open up very exciting possibilities for problem-solving and planning. In everyday applications, we’re talking about Google Voice or Siri becoming the most effective PA imaginable. But in more important contexts, we might be fortunate to consult with robot physicians who save far more lives than is currently the case, perhaps with the help of nano-bots that repair cell damage from inside the body.

While many AI applications, such as driverless cars or Watson, offer societal benefits, robot caregivers arguably could damage ideas of collective responsibility for vulnerable people or erode filial responsibilities and make people less caring. Do you think that’s a valid concern? That as we outsource more of the jobs we don’t like, we lose our humanity?

Part – I’d say most – of what we currently value about human interaction has been driven by the ways in which we’ve been forced, by circumstance, ability, environment, to engage with people. In other words, I don’t think it’s necessarily the case that those relationships of feelings of commonality are connected to the ways in which we currently care for people. We need to avoid reifying these ideas into very particular forms. Speaking for myself, if I were living with a terminally-ill loved one, I can imagine my relationship with that person being enhanced by someone else performing various unpleasant tasks, which would mean that the time I spent with that person could be of a higher quality.

More generally, we’ve always outsourced jobs we don’t like to machines (or to poor people, of course) – I don’t see how this is a qualitatively different situation from the one we’re already in, rather than just another step on a continuum. Those who argue that these AI applications will cost us some humanity need to accept the burden of proof, and demonstrate that the new situations are incomparable to the old.

Joseph Conrad wrote, in Heart of Darkness, “I don’t like work — no man does — but I like what is in the work — the chance to find yourself. You own reality — for yourself not for others — what no other man can ever know. They can only see the mere show, and never can tell what it really means.” Do we impoverish our experience or fundamentally alter who we are by outsourcing less enjoyable work?

Much of what I said in response to the question above applies here also. We can’t restrict ourselves to one model of work, or certain sorts of activity, to find meaning – and never have. We’ve always adapted to different situations, and found whatever meaning we can in what it is that we’re engaged with. And optimistically, when we’re freed from running on various hamster-wheels, we might find forms of meaning that we never imagined existed.

Earlier today, Eusebius McKaiser invited me to join him in a half-hour conversation on critical thinking – how we should do it, and how we fail. Seeing as I happened to be in Johannesburg, I was able to join him at the PowerFM studios for the conversation that ensued, which proved to be far more interesting – for me, at least! – than the more typical interview by telephone. For those interested in the topic, the Soundcloud podcast is embedded below.

Earlier today, Eusebius McKaiser invited me to join him in a half-hour conversation on critical thinking – how we should do it, and how we fail. Seeing as I happened to be in Johannesburg, I was able to join him at the PowerFM studios for the conversation that ensued, which proved to be far more interesting – for me, at least! – than the more typical interview by telephone. For those interested in the topic, the Soundcloud podcast is embedded below.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/166178402″ params=”auto_play=true&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”300″ iframe=”true” /]

I first heard about “the trolley problem” as an undergraduate philosophy student in 1991, as one of the countless thought-experiments moral philosophy uses to probe our intuitions regarding right and wrong, and whether we are consistent in our judgements of what is right/wrong. The problem, for those of you who don’t know it, is presented by its creator (Philippa Foot) as follows:

I first heard about “the trolley problem” as an undergraduate philosophy student in 1991, as one of the countless thought-experiments moral philosophy uses to probe our intuitions regarding right and wrong, and whether we are consistent in our judgements of what is right/wrong. The problem, for those of you who don’t know it, is presented by its creator (Philippa Foot) as follows:

Suppose that a judge or magistrate is faced with rioters demanding that a culprit be found guilty for a certain crime and threatening otherwise to take their own bloody revenge on a particular section of the community. The real culprit being unknown, the judge sees himself as able to prevent the bloodshed only by framing some innocent person and having him executed.

Beside this example is placed another in which a pilot whose aeroplane is about to crash is deciding whether to steer from a more to a less inhabited area. To make the parallel as close as possible it may rather be supposed that he is the driver of a runaway tram which he can only steer from one narrow track on to another; five men are working on one track and one man on the other; anyone on the track he enters is bound to be killed. In the case of the riots the mob have five hostages, so that in both examples the exchange is supposed to be one man’s life for the lives of five.

Those of you who watch football might have heard of Luis Suarez, and in particular of his habit (if three instances counts as a habit) of occasionally biting opponents in the heat of battle. I want to briefly offer a distinction for your consideration, because – as is so often the case on social media – the reactions to his most recent offence have tended towards the hysterical.

The most recent offence occurred in a World Cup game where Uruguay beat (and in consequence, eliminated) Italy. Suarez. The video below clearly shows Suarez lining himself up for a chomp at Chiellini’s shoulder, and Fifa are currently discussing how long Suarez should be banned for (6000 has the scoop on that, by the way).

There’s no question that Suarez deserves sanctions of some sort. And this is where the distinction comes in: one can – and should – separate the issue of what a proportionate punishment would be from the issue of whether we’re treating this case as we treat similar (or worse) offences.

Just like in the last World Cup, when Suarez handballed against Ghana, some folk seem to want him hung, drawn and quartered. The reaction was disproportionate then, especially in South Africa, perhaps thanks to our bizarre adoption of Ghana as our surrogate team. Suarez is a nasty piece of work, as far as I can tell – there’s the three instances of biting, the racism, and the fact that he’s rather good yet plays for Liverpool.

But despite this, we shouldn’t let the fact that biting someone seems particularly strange – animalistic – obscure the fact that biting someone is a far less serious offence than repeated violent play, of the sort that can break legs and end careers. Our reactions to Suarez are inconsistent with our reactions to other serial offenders, who offend in ways other than biting.

Take Pepe as example, with reference to the video below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CFSMICJxZ-Y

Pepe attracts cards fairly frequently – 42 yellow cards and 5 red cards over the years 2008 to 2012 – as one might expect after watching that clip. Yet while the intensity and regularity of his violence attract comment from football fans along the lines of “he’s a dirty bastard” or what have you, I don’t see many people calling for a lifetime ban or many months of suspension.

But tell me: would you rather play against Suarez, with the possibility that he might take a bite of your arm or shoulder, or against Pepe, who might kick you in the head while you’re lying on the turf? As disreputable as Suarez might be – and this fantastic ESPN profile is worth a read, to see his history in this regard, as well as the lengths people go to to defend him – his offences are more notable for their sheer oddity than for their brutality, and we should keep this in mind when calling for his head.